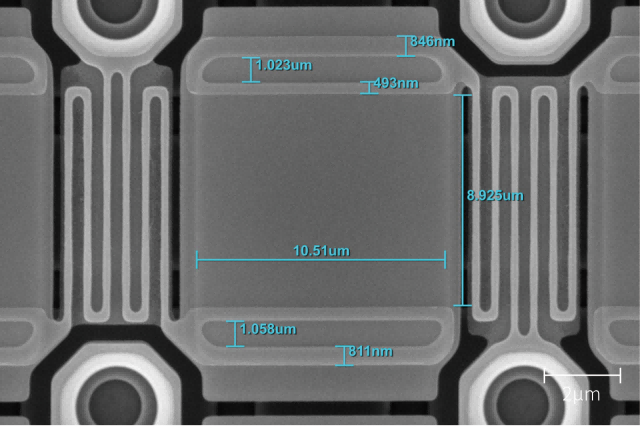

- Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope manufacturer global supplier

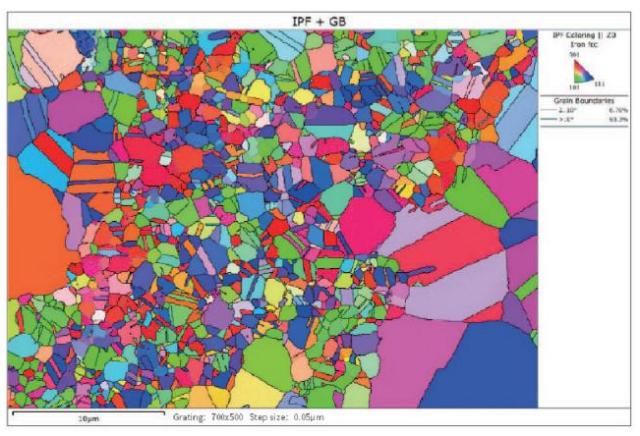

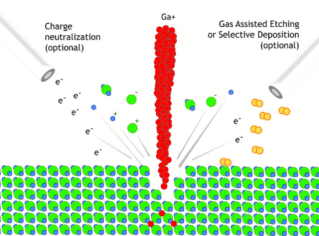

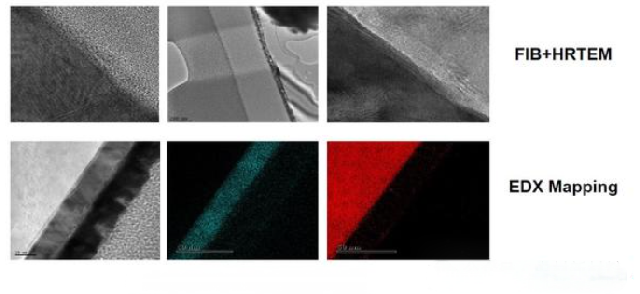

- SEM EDX, EDS, EBSD, BSE, CL, STEM detectors

- scanning nv magnetometer applications

- scanning nv center microscope

- scanning nv magnetometry supplier

- x band electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

- electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy

- epr spectroscopy with cryostat

- w band epr spectrometer

- epr technology